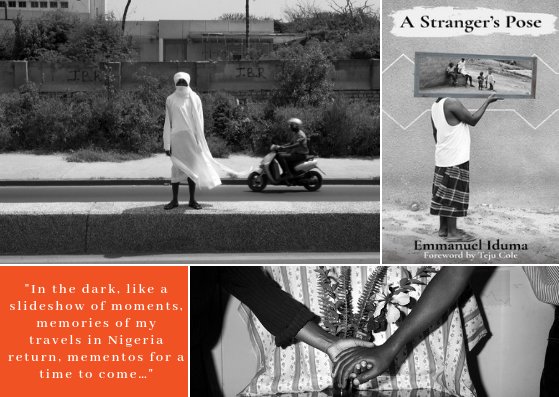

Between August 30, 2017 and December 13, 2017, writer and art critic Emmanuel Iduma shared a series of vignettes and images on his Instagram page - with the hashtag #astrangerspose. In that period around 23 of these photos and vignettes were shared. Less than one year later, some of these images appear in Emmanuel Iduma's soon-to-be released book, A Stranger's Pose.

|

| What appears to be the first image in Emmanuel Iduma's #astrangerspose series on Instagram |

Published by Cassava Republic, and out in Nigeria and the UK October 16, 2018 and in the US November 17, 2018, A Stranger's Pose has been described as "an evocative and mesmerising account of travels across different African cities". The blurb further describes it as "a unique blend of travelogue, musings and poetry".

A Stranger's Pose begins in Mauritania. Emmanuel Iduma is "in a white E350 Ford van ... driv[ing] into a Mauritanian sunset"

This first chapter is half a page. Half a page is enough to clearly inform you of what you are getting into when you decide to read A Stranger's Pose. By Chapter 2 - which is probably around three-quarters of a page long - we meet "a relative who requested anonymity". A relative who after Iduma recounted stories of his travels asked him to "take me with you on your journeys". Simply put - this is exactly what Emmanuel Iduma does with A Stranger's Pose. Through poetic writing, Iduma takes you along on the journey. You feel like you are there - on these different journeys - every step of the way.

Through Iduma's travels, we go to Mauritania, Lome (as part of a West African book tour), Kouserri (twenty-five kilometres from N'djamena), as well as N'djamena, Dakar, Rabat, Nouakchott, Bamako, Abidjan, Addis Ababa, Douala, Yaounde, Nouadhibou, Khartoum, Goree Island. In Nigeria, we go to Lagos, Benin City, Abuja, Asaba, Umuahia, Enugu. I haven't captured all the places we encounter. A map in the middle of the book helps us place the different African countries and cities Emmanuel Iduma visits during his travels.

Iduma meets many people along the way. People whose stories are as much a part of A Stranger's Pose as Iduma's own stories. Khadija who worked in the building he was residing while in Rabat, Serge the caretaker of the motel he stayed at in Abidjan, Salih in Mauritania who lives alone, and will not get married as "women are too complicated". These are some of the people we meet.

The story - the journey - isn't linear. Then again, neither are our memories, and the ways in which we remember things and tell our stories. We may start off in Mauritania, then head off to Lome, and many pages later we are back in Mauritania. This is what also makes it feel like Iduma is telling only you a story - as he remembers it, or should I say recounts it. That is, his travels - be it difficult experiences, such as obtaining visas or something unique/beautiful about that city he visited, or the period at which he visited the place, or the person(s) he encountered on this trips.

Iduma is very observant. The things he notices and captures in the book make you aware of just how. Iduma is able to capture not only the sense of a place, but also the sense of people in those places he visits and even their moods and their feelings. A Stranger's Pose also gives a sense of be/longing. How do you get to and from a place? Especially if you are an African (a Nigerian) visiting other countries in Africa? What is it really like to be in a place where you don't understand the language? How do you navigate these spaces?

At the same time, this book is more than observations of a young Nigerian man travelling within Nigeria, and across a number of African cities. In some parts, it also feels like a book about searching - especially in the chapters focused on "home" (by home, I am referring to Nigeria). A Stranger's Pose doesn't end far away, but closer to home - in Iduma's ancestral hometown. I won't give away too much, but Iduma is searching for something and towards the end writes a passage that made me think not only of a stranger's pose but a stranger's glance.

I am yet to mention the photographs that accompany this book - around 40 if I counted correctly. Photographs taken by Siaka Traore, Tom Saater, Dawit L. Petros, Abraham Oghobase, Jide Odukoya, Emeka Okereke, Stephen F. Sprague, Adeola Olagunju, Eric Gottesman, Paul Marty, Michael Tsegaye, and Emmanuel Iduma himself. Forty photographs that also stay with you long after you finish the book.

Emmanuel Iduma is an art critic, and if you have read his photo essays, such as The Colonizer's Archive is a Crooked Finger, it makes sense that photographs would feature in this book. For me the photographs also made me remember the stories even more. I am struggling to find the right words to describe it. For now I will say, it humanised an already very human story. Still, I want to know how, and why, the photographs were selected? Did the vignettes/stories come first, and photos come after? Or did the photographs jog a specific memory that Emmanuel Iduma was then compelled to write?

I also haven't touched on the books mentioned in this book - including Yvonne Owuor's Dust, Ben Okri's Famished Road, Amos Tutuola's My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, John Berger's Photocopies, Breyten Breytenbach's Intimate Strangers. There are also a few films mentioned in this book.

Travel writing - particularly in the African context - tends to be dominated by a Western perspective. Indeed, back in 2013, Fatimah Kelleher wrote about travel writing and Africa in the 21st century

I don't tend to quote myself, but I end with something I tweeted after I finished A Stranger's Pose:

Today Eid ul-Fitr begins. Men are walking back from mosques, women and children trailing them, sure-footed celebratory. I see all this with my nose pressed to the window. The men wear long, loose-fitting garments, mostly white, sometimes light blue. I watch them from behind, and think of the word 'swashbuckle'. I am moved by these swaggering bodies, dressed in their finest, walking to houses that look only seven feet high. I envy the ardour in their gait, a lack of hurry, as if by walking they possess a piece of earth.

I want to be these men.

This first chapter is half a page. Half a page is enough to clearly inform you of what you are getting into when you decide to read A Stranger's Pose. By Chapter 2 - which is probably around three-quarters of a page long - we meet "a relative who requested anonymity". A relative who after Iduma recounted stories of his travels asked him to "take me with you on your journeys". Simply put - this is exactly what Emmanuel Iduma does with A Stranger's Pose. Through poetic writing, Iduma takes you along on the journey. You feel like you are there - on these different journeys - every step of the way.

Through Iduma's travels, we go to Mauritania, Lome (as part of a West African book tour), Kouserri (twenty-five kilometres from N'djamena), as well as N'djamena, Dakar, Rabat, Nouakchott, Bamako, Abidjan, Addis Ababa, Douala, Yaounde, Nouadhibou, Khartoum, Goree Island. In Nigeria, we go to Lagos, Benin City, Abuja, Asaba, Umuahia, Enugu. I haven't captured all the places we encounter. A map in the middle of the book helps us place the different African countries and cities Emmanuel Iduma visits during his travels.

Iduma meets many people along the way. People whose stories are as much a part of A Stranger's Pose as Iduma's own stories. Khadija who worked in the building he was residing while in Rabat, Serge the caretaker of the motel he stayed at in Abidjan, Salih in Mauritania who lives alone, and will not get married as "women are too complicated". These are some of the people we meet.

The story - the journey - isn't linear. Then again, neither are our memories, and the ways in which we remember things and tell our stories. We may start off in Mauritania, then head off to Lome, and many pages later we are back in Mauritania. This is what also makes it feel like Iduma is telling only you a story - as he remembers it, or should I say recounts it. That is, his travels - be it difficult experiences, such as obtaining visas or something unique/beautiful about that city he visited, or the period at which he visited the place, or the person(s) he encountered on this trips.

Iduma is very observant. The things he notices and captures in the book make you aware of just how. Iduma is able to capture not only the sense of a place, but also the sense of people in those places he visits and even their moods and their feelings. A Stranger's Pose also gives a sense of be/longing. How do you get to and from a place? Especially if you are an African (a Nigerian) visiting other countries in Africa? What is it really like to be in a place where you don't understand the language? How do you navigate these spaces?

At the same time, this book is more than observations of a young Nigerian man travelling within Nigeria, and across a number of African cities. In some parts, it also feels like a book about searching - especially in the chapters focused on "home" (by home, I am referring to Nigeria). A Stranger's Pose doesn't end far away, but closer to home - in Iduma's ancestral hometown. I won't give away too much, but Iduma is searching for something and towards the end writes a passage that made me think not only of a stranger's pose but a stranger's glance.

I am yet to mention the photographs that accompany this book - around 40 if I counted correctly. Photographs taken by Siaka Traore, Tom Saater, Dawit L. Petros, Abraham Oghobase, Jide Odukoya, Emeka Okereke, Stephen F. Sprague, Adeola Olagunju, Eric Gottesman, Paul Marty, Michael Tsegaye, and Emmanuel Iduma himself. Forty photographs that also stay with you long after you finish the book.

|

| One of the photographs that feature in A Stranger's Pose. Source: Slideshare |

Emmanuel Iduma is an art critic, and if you have read his photo essays, such as The Colonizer's Archive is a Crooked Finger, it makes sense that photographs would feature in this book. For me the photographs also made me remember the stories even more. I am struggling to find the right words to describe it. For now I will say, it humanised an already very human story. Still, I want to know how, and why, the photographs were selected? Did the vignettes/stories come first, and photos come after? Or did the photographs jog a specific memory that Emmanuel Iduma was then compelled to write?

I also haven't touched on the books mentioned in this book - including Yvonne Owuor's Dust, Ben Okri's Famished Road, Amos Tutuola's My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, John Berger's Photocopies, Breyten Breytenbach's Intimate Strangers. There are also a few films mentioned in this book.

Travel writing - particularly in the African context - tends to be dominated by a Western perspective. Indeed, back in 2013, Fatimah Kelleher wrote about travel writing and Africa in the 21st century

Over the last 400 years however, travel literature has been dominated by western colonial and post-colonial viewpoints (which in turn have been dominated by the upper and middle classes) that have contributed to the larger lens through which places like Africa are viewed globally.Kelleher followed this up in 2014 with a reading list of ten African and African Diaspora travel writing - some of which were included in a 2014 list on African travel writing for this blog. It is extremely refreshing to read writing about travels on the African continent by an African - in this case a Nigerian. With Emmanuel Iduma's book adding to a canon of travel memoirs/books that are slowly moving the genre - when it comes to writing about 'Africa' - away from the Western gaze.

I don't tend to quote myself, but I end with something I tweeted after I finished A Stranger's Pose:

I savoured every word, every sentence, every paragraph, every image. As I got to the last line of the last page ... the only word I have in my vocabulary to describe this book is 'beautiful'.